It seems these days there are countless methodologies, processes and practices to choose from when developing software and, somewhat ironically, the list seems to be growing at the rate of Moore’s law. I’ve read about, discussed, been on courses and been to conferences about a lot of them and the thing I’ve consistently found most useful is talking to other practitioners about what they’re doing and what’s working (or not working) for them.

Recently there’s been a lot of (and subsequently criticism of) debate on message boards and blogs about the relative benefits of one paradigm versus the other. Personally I don’t care much for subscribing to any particular paradigm and am much more interested in what works and what doesn’t (and in which circumstances) so my response is to publish what my team and company is actually doing right now. This is a snapshot of our current practices. Ask me again in 6 months and hopefully I’ll show you something very different.

The inspiration and influences for the way we work mostly come from Agile, Scrum, Extreme Programming, Software Craftsmanship, Lean, Lean Software Development, Kanban Software Development and The Toyota Way. It is all and none of these things.

Context

We are a small to medium size “start up” organisation working in the new media industry. The company employs around 60 people mainly based in the UK. The development department numbers around 20 co-located people. Agile practices are a relatively new introduction and the previous approach was of the typically chaotic type familiar to young businesses. Â We mainly work in .Net using C# but also dabble in Ruby, Javascript and UI languages. The rest of the article mostly relates specifically to one of the teams working within the department but also addresses some of the practices of the department as a whole.

Team

The team is made up of 4-5 developers and a tester. There is no project manager at the team level – in the spirit of self-organisation (principle 11)Â the duties traditionally the responsibility of a PM are shared between the team members. The Product Owner role is shared between the stakeholders within the organisation for the products the team is responsible for.

Iterations

We currently work in 1 week Iterations. It’s a new team who are also new to many of the agile concepts and doing this enables us to control the amount of work in progress, focus on delivery, improve our discipline and most importantly have short feedback cycles so improvements can be discussed and applied frequently. The downside is the overhead created by the amount of meetings. Once we’re comfortable the team is working well together we will have the opportunity to change this if desired (e.g. Continuous Flow, changing the iteration length, changing the frequency of meetings).

Meetings

Each iteration we have the following meetings:

Work Prioritisation – occurs iteration minus one. Stakeholders come together to raise and prioritise work not yet commited to.

Requirements Gathering – occurs ad hoc when necessary. All the team is required to attend along with the customer/s to bash out requirements for work prioritised in the prioritisation meeting.

Planning – occurs at the beggining of the iteration. Prioritised features (MMFs) which have been analysed are broken down into stories, discussed, estimated and commited to based on our current velocity (avg. over last 6 weeks)

Stand Up – occurs daily at 10am at the task board. Anyone outside the team is welcome to watch

Retrospective – occurs at the end of the iteration. Any actions from the meeting are to be completed by the end of the next iteration.

Requirements

Features are requested at the prioritisation session and use the User Story format.

More detailed requirements are gathered during the requirements meetings mentioned above, with the customer/s and all team members present. We use whiteboards to bash out the requirements and convert them into acceptance criteria using the “Given, When, Then” format. We have a rule that no work can be commited to unless we’re happy we have a clear understanding of the requirements.

Task Board

The task board is essentially a Kanban board with each stage of the delivery process separated into columns. We have an implicit limit of 2 stories in active, but otherwise have not applied limits to any other columns. Features (MMF) are blue, the stories which make up the MMFs are yellow, bugs are pink and quick support tasks white. When a story is commited to, the feature card is moved into “commited”, above the titles of the columns and tracks the last related story.

Measurement & Metrics

We use an Excel spreadsheet to hold the product backlog and track the data from the Kanban/Task board. Whenever an MMF moves to another column the date this occured is recorded. You can download a copy of the spreadsheet here (you may want to check the calcs on the CFD, not sure they’re right). Among other things it calculates average cycle time, average velocity and projections based on velocity. I’ve tried a few bespoke tracking tools (such as Mingle) and found nothing is as powerful and flexible as Excel.

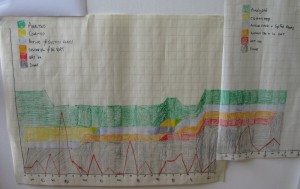

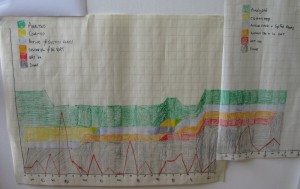

We have a manual Cumulative Flow Diagram (CFD) which each team member takes turns to update daily so everyone shares the responsibility (it is also their job to update the Excel spreadsheet each day). The CFD diagram only tracks the value delivered to the business (one unit = one MMF. Measure the output, not the input) and is also represented in the Excel spreadsheet. Why have both you may ask? Visibility.

We have some rudamentry code metrics set up through our continuous integration framework such as NDepend output and test coverage but are working towards something more visible and useful.

Estimation

Still very much a necessary evil.

For comitting to work for an iteration we use Story Points using the fibonacci (1, 2, 3, 5, 8…) sequence and achieve them by playing Planning Poker with everyone who may be involved in the work required to take part. We will only estimate (and commit to) work we have already analysed and gathered requirements for.

For longer term planning, as we don’t yet have enough information to be able to use cycle time for projecting work completion, using the velocity based on points completed per iteration has proven a very powerful toool to be able to give the rest of the business a better idea of our capacity and timescales (previously they had none). However this has well known drawbacks and we must be careful it does not get abused, as I have seen before (such as gaming of estimates, whether intentionally on subconsciously). Also, as we need to understand and have gathered the requirements to be able estimate this way it means there is very limited scope to how far into the future we can do this with any degree of confidence (as requirements will change). Once we have a reasonable amount of data in the system we will be able to use average cycle time, which will be much more powerful.

Coding Practices

Apart from the rules we’ve commited to as a team, Pair Programming, Unit Testing, Refactoring and the best working principles and practices of the software industry are encouraged from the top of the department and applied rigorously but pragmatically.

At the request of the department members (as a result of a disucssion on collective responsibility) we created a development standards document which includes topics such as naming conventions and testing. As much as possible the document is vague on implementation details to prevent it from holding us back when better working practices come along. We use shared Resharper and Visual Studio settings to help us keep to these standards.

As mentioned below we also frequently hold sessions to improve our skills.

Automated Testing

All new or modified code is covered by unit tests, integration tests (such as database interaction) and automated acceptance tests which test against the acceptance criteria (this last one is quite new territory).

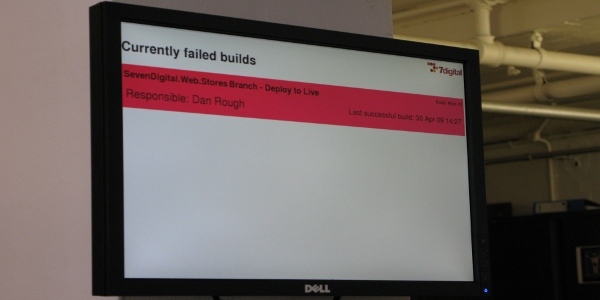

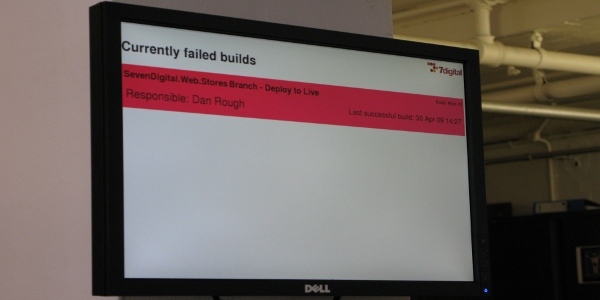

All projects are under continuous integration (we use TeamCity) and we are working towards having all deployments doing the same. We have monitors on the wall which show all the currently failing builds. Do I need to mention we use source control?

Roles and Responsibilities

Every role in the department is covered by a document explaining their roles and responsibilities. They are written in a way which encourages self-organisation and collective responsiblity. You can download them here. I will be talking about these descriptions more in a future article.

Each week two hours are set aside for learning sessions such as coding dojos and presentations (we’re currently running a design patterns study group). Outside of these developers are actively encouraged to take the time to learn new practices during working hours (within reason). We have a library of books available on a range of subjects which are at the disposal of everyone. More often than not if there’s a book that someone would like to read the company will purchase it and add it to the library (books are pretty cheap in the grand scheme of things).

Outside of retrospectives we have a monthly departmental session where the most pressing problems are discussed and actions taken away. However there is no limit or retriction to when improvements can be made and everyone is encouraged to take the initiative when they see a problem that needs addressing.