It’s helpful to get a view of what’s actually happening on the ground rather than the broader industry hype. I’m in quite a few CTO and Tech Leader forums, so I thought I’d do something GenAI is quite good at – collate and summarise conversation threads and identify common themes and patterns.

Here’s a consolidated view of the observations, patterns and experiences shared by CTOs and tech leaders across various CTO forums in the last couple of months

Disclaimer: This article is largely the output from my conversation with ChatGPT, but reviewed and edited by me (and as usual with GenAI, it took quite a lot of editing!)

Adoption on orgs is mixed and depends on context

- GenAI adoption varies significantly across companies, industries and teams.

- In the UK, adoption appears lower than in the US and parts of Europe, with some surveys showing over a third of UK developers are not using GenAI at all and have no plans to1UK developers slow to adopt AI tools says new survey.

- The slower adoption is often linked to:

- A more senior-heavy developer population.

- Conservative sectors like financial services, where risk appetite is lower.

- The slower adoption is often linked to:

- Teams working in React, TypeScript, Python, Bash, SQL and CRUD-heavy systems tend to report the best results.

- Teams working in Java, .NET often find GenAI suggestions less reliable.

- Teams working in modern languages and well-structured systems, are adopting GenAI more successfully.

- Teams working in complex domains, messy code & large legacy systems often find the suggestions more distracting than helpful.

- Feedback on GitHub Copilot is mixed. Some developers find autocomplete intrusive or low-value.

- Many developers prefer working directly with ChatGPT or Claude, rather than relying on inline completions.

How teams are using GenAI today

- Generating boilerplate code (models, migrations, handlers, test scaffolding).

- Writing initial tests, particularly in test-driven development flows.

- Debugging support, especially for error traces or unfamiliar code.

- Generating documentation

- Supporting documentation-driven development (docdd), where structured documentation and diagrams live directly in the codebase.

- Some teams are experimenting with embedding GenAI into CI/CD pipelines, generating:

- Documentation.

- Release notes.

- Automated risk assessments.

- Early impact analysis.

GenAI is impacting more than just code writing

Some teams are seeing value beyond code generation, such as:

- Converting meeting transcripts into initial requirements.

- Auto-generating architecture diagrams, design documentation and process flows.

- Enriching documentation by combining analysis of the codebase with historical context and user flows.

- Mapping existing systems to knowledge graphs to give GenAI a better understanding of complex environments.

Some teams are embedding GenAI directly into their processes to:

- Summarise changes into release notes.

- Capture design rationale directly into the codebase.

- Generate automated impact assessments during pull requests.

Where GenAI struggles

- Brownfield projects, especially those with:

- Deep, embedded domain logic.

- Where there is little or inconsistent documentation.

- Highly bespoke patterns.

- Inconsistent and poorly structured code

- Languages with smaller training data sets, like Rust.

- Multi-file or cross-service changes where keeping context across files is critical.

- GenAI-generated code often follows happy paths, skipping:

- Error handling.

- Security controls (e.g., authorisation, auditing).

- Performance considerations.

- Several CTOs reported that overly aggressive GenAI use led to:

- Higher defect rates.

- Increased support burden after release.

- Large, inconsistent legacy codebases are particularly challenging, where even human developers struggle to build context.

Teams are applying guardrails to manage risks

Many teams apply structured oversight processes to balance GenAI use with quality control. Common guardrails include:

- Senior developers reviewing all AI-generated code.

- Limiting GenAI to lower-risk work (boilerplate, tests, internal tooling).

- Applying stricter human oversight for:

- Security-critical features.

- Regulatory or compliance-related work.

- Any changes requiring deep domain expertise.

The emerging hybrid model

The most common emerging pattern is a hybrid approach, where:

- GenAI is used to generate initial code, documentation and change summaries, with final validation and approval by experienced developers.

- Developers focus on design, validation and higher-risk tasks.

- Structured documentation and design rules live directly in the codebase.

- AI handles repetitive, well-scoped work.

Reported productivity gains vary depending on context

- The largest gains are reported in smaller, well-scoped greenfield projects.

- Moderate gains are reported more typical in medium to large, established or more complex systems.

- Neutral to negative benefit in very large codebases, messy or legacy systems

- However, across the full delivery lifecycle, a ~25% uplift is seen as a realistic upper bound.

- The biggest time savings tend to come from:

- Eliminating repetitive or boilerplate work.

- Speeding up research and discovery (e.g., understanding unfamiliar code or exploring new APIs).

- Teams that invest in clear documentation, consistent patterns and cleaner codebases generally see better results.

Measurement challenges

- Most productivity gains reported so far are self-reported or anecdotal.

- Team-level metrics (cycle time, throughput, defect rates) rarely show clear and consistent improvements.

- Several CTOs point out that:

- Simple adoption metrics (e.g., number of Copilot completions accepted) are misleading.

- Much of the real value comes from reduced research time, which is difficult to measure directly.

- Some CTOs also cautioned that both individuals and organisations are prone to overstating GenAI benefits to align with investor or leadership expectations.

Summary

Across all these conversations, a consistent picture emerges – GenAI is changing how teams work, but the impact varies heavily depending on the team, the technology and the wider processes in place.

- The biggest gains are in lower-risk, less complext, well-scoped work.

- Teams with clear documentation, consistent patterns and clean codebases see greater benefits.

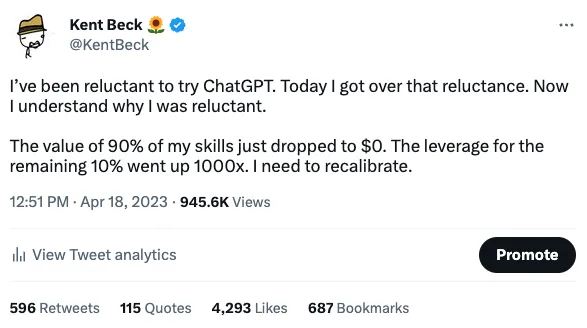

- GenAI is a productivity multiplier, not a team replacement.

- The teams seeing the most value are those treating GenAI as part of a broader process shift, not just a new tool.

- Long-term benefits depend on strong documentation, robust automated testing and clear processes and guardrails, ensuring GenAI accelerates the right work without introducing unnecessary risks.

The overall sentiment is that GenAI is a useful assistant, but not a transformational force on its own. The teams making meaningful progress are those actively adapting their processes, rather than expecting the technology to fix underlying delivery issues.