This is a cross post of an article I wrote for Ada, the National College for Digital Skills

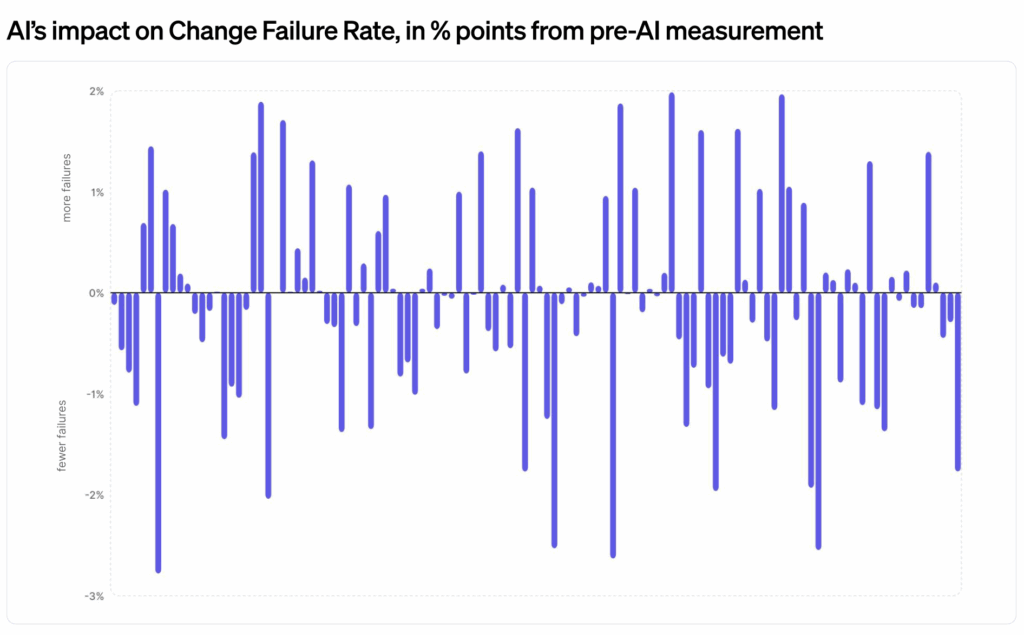

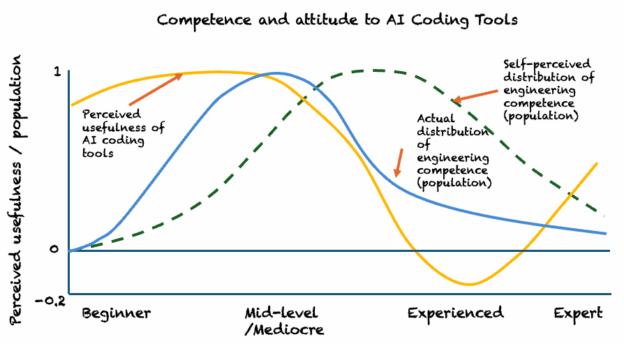

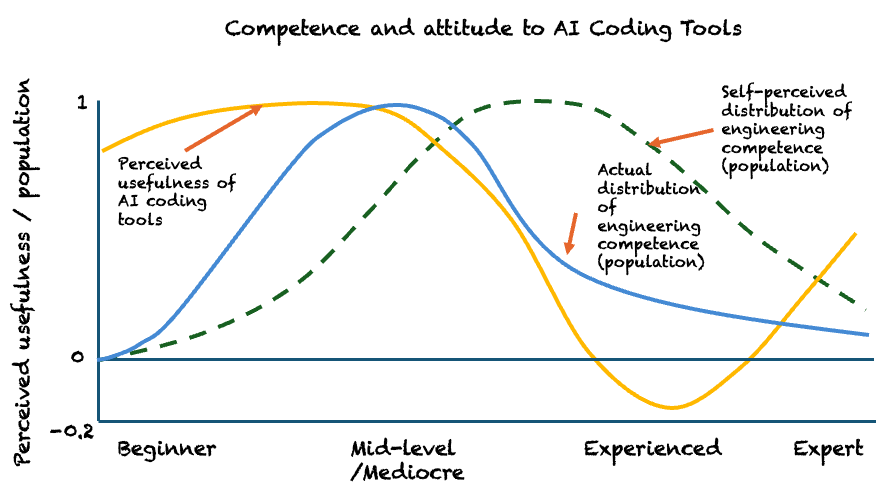

All the available evidence suggests that GenAI-assisted coding is most powerful in the hands of highly experienced software engineers, while having neutral or even negative effects for less experienced ones.

It’s easy to see how this may be interpreted inside organisations. If experienced engineers can be made significantly more productive with GenAI, then it can appear rational to rely more heavily on that group. Smaller teams of senior engineers, supported by GenAI, with fewer junior or entry-level roles, can look like an attractive opportunity.

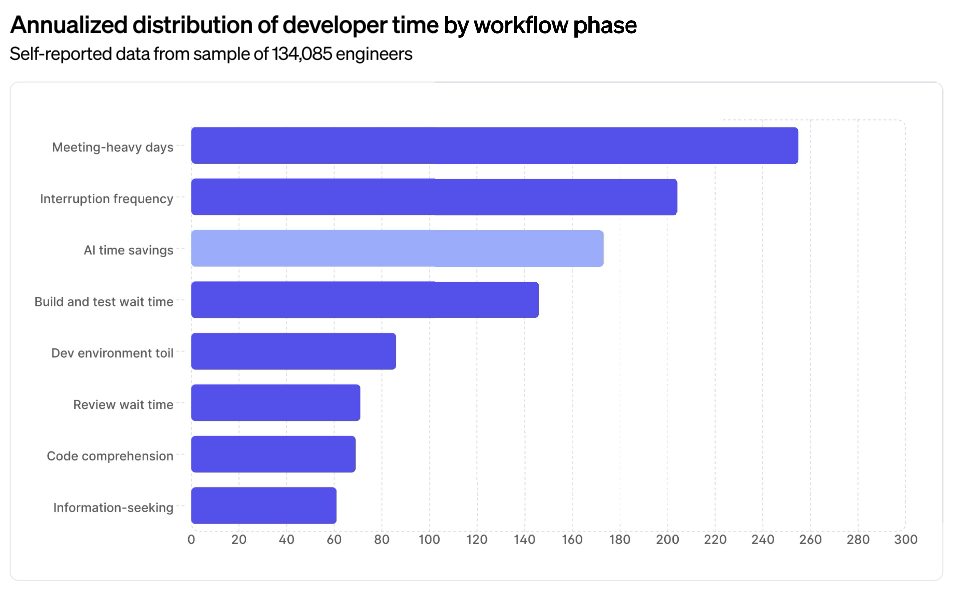

However, genuinely good, experienced software engineers are already scarce across the industry. It is difficult to put a precise figure on this, but studies on the impact of AI in software engineering suggest that only a minority of engineers and teams currently have the skills and experience needed to realise sustained benefits from GenAI-assisted software development, likely somewhere in the region of 10–30%.

That raises an obvious question about where the next generation of experienced engineers will come from.

The risk is not only that organisations hire fewer junior engineers, but that even when they do, the conditions for learning are compromised. A recent study by Anthropic, one of the organisations at the frontier of GenAI and the creators of the Claude models and tools such as Claude Code, found that developers using AI assistance completed coding tasks slightly faster but demonstrated significantly weaker understanding afterwards. When the tool was allowed to do too much of the thinking, learning suffered.

More generally, as organisations offload more work to these tools, team dynamics begin to shift. Fewer questions are asked. Explanation gives way to acceptance. Output rises, but shared understanding does not.

This all happens quietly. Everything looks efficient, right up until it’s not.

Despite repeated waves of tooling, the core skills that define good software engineering have remained remarkably stable. Effective problem-solving, system-level thinking, feedback, shared understanding, automated testing and iterative change have been recognised as good practice for decades.

Learning is not just an individual concern. Software development is a learning activity at every level. Teams learn about users, systems, risks, and constraints through the work itself.

What has also remained true, despite this being well understood, is that only a minority of the industry consistently applies them. The evidence also increasingly suggests these practices are becoming even more relevant in the age of GenAI.

GenAI accelerates this dynamic. Without deliberate effort, it can speed up delivery while quietly weakening an organisation’s ability to create and sustain expertise. When organisations optimise purely for short-term efficiency, learning is often the first thing to erode. When learning slows, capability follows.

The organisations that will thrive in the GenAI era will not be the ones that simply adopt the tools. They will be the ones that treat learning as core to how they operate.

That includes investing in early-career development, creating environments where experience is accumulated rather than bypassed, and recognising that effective software development has always depended on people who can exercise judgement, reason about systems, and learn continuously, not just produce output.