I’ve written up an experience report on my recent adventures trying to improve the way we do pay reviews (it’s more interesting than you might think).

Like many companies we’ve been struggling with a problematic pay review process. In our case the feedback mainly revolved around it feeling arbitrary and lacking transparency. Around the time we were discussing this the Valve Handbook got posted, within which it talked about their peer review & stack ranking system:

“We have two formalized methods of evaluating each other: peer reviews and stack ranking. Peer reviews are done in order to give each other useful feedback on how to best grow as individual contributors. Stack ranking is done primarily as a method of adjusting compensation. Both processes are driven by information gathered from each other—your peers.”

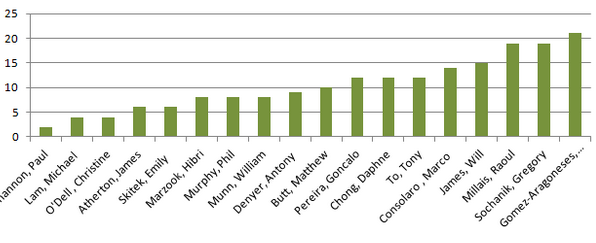

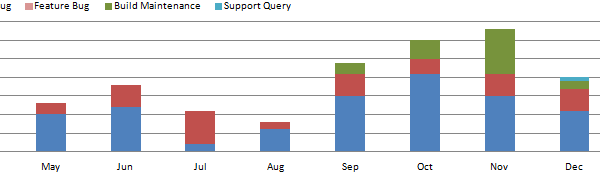

Awesome, you get rated by your peers rather than a manager or HR person, who has no idea what you do (not that we did that anyway)! I liked this idea a lot and got to work on doing our own version. I started with a trial peer review survey with one team. There were some positives, but it mostly went down badly. People really didn’t like the stack ranking and also that I only asked a few high level questions with the answer being a score out of 10. So we went back to the drawing board. We got representatives from all our teams and held 4/5 sessions where we broke down the larger themes (Skill, Productivity, Communication, Team) into more detailed and objective questions. After a lot of persistence and effort we finally put this all together and we had the survey! Which I promptly canned…

Trying to measure performance

The fundamental problem I was (naïvely) trying to solve with a peer review survey was to bring in a degree of measurement, which would hopefully mean people felt the pay review process had a quantifiable aspect and didn’t just come down to one person’s opinion. However we were getting into the terrain of incentivising our people based on individual optimisations (rather than organisational or team goals & objectives) and – most disturbingly – the anonymous feedback aspect just felt very wrong. It was and is completely contrary to our culture and the things we stand for. The trade-offs simply weren’t worth it. Regardless of the unpleasantness of anonymous feedback, everywhere I’ve heard of using ranking/measurement schemes have really bad stories to tell, such as Microsoft and GE. Warning signs everywhere.

Don’t mix pay reviews with feedback

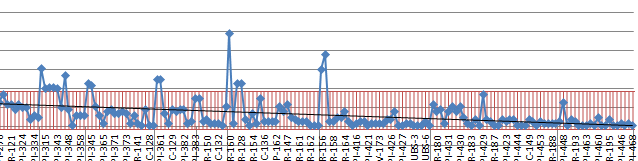

Another problem is the survey would have been a kind of feedback mechanism. Imagine getting your results – all nicely presented in bar charts – and finding you scored really badly on one section. What the heck are you supposed to do with that?! I’m a really bad communicator? What do they mean by that? Who thinks that? Great, everyone thinks I’m rubbish but I’ve got no way of finding out why apart from going around everyone and asking them. Ouch! I am a big believer in regular 1-2-1s (I’ve talked about them a bit here). As Head of Development I start every day with a 1-2-1 with one of my department (I see all 35+ people as regularly as I can). Each team also does 1-2-1s (usually with their Lead if they have one). Each new joiner gets a mentor who they have a monthly 1-2-1 with for their first 3-6 months. By the time you get to a pay review their should be no surprises, no feedback that you haven’t already heard before.

Where we are now

Our latest attempt is heavily based (& in some parts very plagiarised, I have to admit) on the StackExchange compensation scheme. The peer review survey wasn’t a complete waste. I adapted the themes and questions from the survey we built into a set of core values we desire from our colleagues to be used for guidance. This is still very new and as yet unproven, but it certainly feels a lot better than where heading previously. I could explain in more detail, but it would be duplicating what I’ve said in the document/guide, which you can download here: 7digital Dev & DBA Team Compensation

Finally, a word on annual performance appraisals

I’ve only been employed by one company who ran annual performance appraisals and was far from impressed. It’s something we’ve consciously avoided for our tech teams at 7digital. I could go into more details as to why they are wrong, but others much more qualified than me have already done so:

- The Paradox of Performance Pay – a really great article/opinion piece by Dr Allan Hawke , a former chief of staff to Australian prime minister Paul Keating, a former federal departmental secretary and a former senior diplomat.

- W. Edwards Demming talking about performance appraisals as one of the five deadly diseases of management. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ehMAwIHGN0Y&feature=youtu.be&t=5m

- An article in HR magazine on a study of British workers showing huge dissatisfaction with how performance appraisals are run. http://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/hr/features/1015028/hr-directors-try-harder-engage-employees-appraisals-process

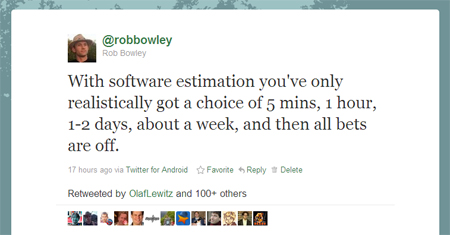

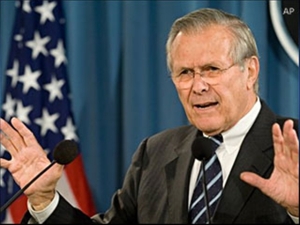

Donald Rumsfeld got soundly mocked for his infamous “unknown unknowns” quote, but he was right. With software development, just like any

Donald Rumsfeld got soundly mocked for his infamous “unknown unknowns” quote, but he was right. With software development, just like any