Introduction

I wrote this guide because I wanted a useful, practical article to share with QA (Quality Assurance) specialists, testers and software development teams, for how to shift away from traditional testing approaches to defect prevention. It’s also based on what I’ve seen work well in practice.

More than that, it comes from a frustration that the QA role – and the industry’s approach to quality in general – hasn’t progressed as much as it should. Outside of a few pockets of excellence, too many organisations and teams still treat QA as an afterthought.

When QA shifts from detecting defects to preventing them, the role becomes far more impactful. Software quality improves, delivery speeds up, and costs go down.

Whilst this guide is primarily aimed at QA specialists and testers looking to move beyond testing into true quality assurance, it’s also relevant to anyone in software development who is interested in faster, more cost-effective delivery of high-quality, reliable software.

The QA role hasn’t evolved

Something similar happened to QA as it did with DevOps. At some point, testers were rebranded QAs, but largely kept doing the same thing. From what I can see, the majority of people with QA in their title are not doing much actual quality assurance.

Too often, QA is treated as the last step in delivery – developers write code, then chuck it over the wall for testers to find the problems. This is slow, inefficient, and expensive.

Inspection doesn’t improve quality, it just measures a lack of it.

Unlike DevOps (which is a collection of practices, culture and tools, not a job title), I believe there’s still a valuable role and place for QA specialists, especially in larger orgs.

QA’s goal shouldn’t be just to find defects, but to prevent them by embedding quality throughout the development process – not just inspecting at the end. In other words, we need to build quality in.

The exponential cost of late defects and delivery bottlenecks

The cost of fixing defects rises exponentially the later they are found. NASA researchconfirms this, but you don’t really need empirical studies to substantiate this, it’s pretty simple:

The later a defect is found, the more resources have been invested. More people have worked on the it, and fixing it involves more rework – it’s easy to tweak a requirement early, but rewriting code, redeploying, and retesting is much more expensive. In production, they impact users, sometimes requiring hotfixes, rollbacks, and firefighting that disrupts everything else. Beyond direct costs, there’s the cumulative cost of delay – the knock-on effect to future work.

Late-stage testing isn’t just costly – it’s often the biggest bottleneck in delivery. Most teams have far fewer QA specialists/testers than developers, so work piles up at feature testing (right after development) and even more at regression testing. Without automation, regression cycles can take days or even weeks.

As a result, features and releases stall, developers start new work while waiting, and when bugs come back, they’re now juggling fixes alongside new development. Changes are batched into large, high risk releases. Increasing the team size can often end up doing little more than excarcerbated the bottlenecks.

It’s an inefficient and expensive way to build software.

The origins of Build Quality In

“Build Quality In” originates from lean manufacturing and the work of W. Edwards Deming and Toyota’s Production System (TPS). Their core message: Inspection doesn’t improve quality – it just measures the lack of it. Instead, they focused on preventing defects at the source.

Toyota built quality in by ensuring that defects were caught and corrected as early as possible. Deming emphasised continuous improvement, process control, and removing reliance on inspection. These ideas have shaped modern software development, particularly through lean and agile practices.

Despite these well-established principles, QA and testing in many teams hasn’t moved on as much as it should have.

From gatekeeper to enabler

Quality assurance shouldn’t be a primarily late stage checkpoint, it should be embedded throughout the development lifecycle. The focus must shift left. Upstream.

This means working closely with product managers, designers, BAs, developers from the start and all the way through, influencing processes to reduce defects before they happen.

Unless you’re already working this way, it probably means working a lot more collaboratively and pro-actively than you currently are.

Be involved in requirements early

QA specialists should be part of requirements discussions from the start. If requirements are vague or ambiguous, challenge them. The earlier gaps and misunderstandings are addressed, the fewer defects will appear later.

Ensure requirements are clear, understood and testable

Requirements should be specific, well-defined, and easy to verify. QA specialists should work with the team to make sure everyone is clear, and be advising on appropriate automated testing to ensure it’s part of the scope.

Tip: Whilst there are some strong views on the benefit of Cucumber and similar acceptance test frameworks, I’ve found the Gherkin syntax very good for specifying requirements in stories/features, which makes it easier for developers to write automated tests and easier for anyone to take part in manual testing

If those criteria are not met, it’s not ready to start work (and it’s your job to say so). Outside of refinement sessions/discussions, I’m a fan of a quick Three Amigos (QA, Dev Product) before a developer is about to pick up a new piece of work from the backlog

Collaborating with developers

QA specialists and developers should collaborate throughout development, not just at the end. This means pairing on tricky areas and automated tests, being available to provide fast feedback (rather than always waiting for work to e.g. be moved to “ready to to test”), having open discussions about risks and edge cases. The earlier QA provides input, the fewer defects make it through.

Encourage effective test automation

QA should help developers think about testability as they write code. Ensure unit, integration, and end-to-end tests as part of the development process, rather than relying on manual testing later. Guide on the most suitable tests to be implementing (see the test pyramid and testing trophy). If a feature isn’t easily testable, that’s a design flaw to address early.

Tip: If you have little or no automated testing, start with high-level end-to-end tests using tools like Playwright. Begin with simple, frequently executed tests from your manual regression pack and gradually build them up. Most importantly, integrate them into your CI/CD pipeline so they run automatically whenever code is deployed.

Work closely with developers to write these tests – shared ownership is essential. Whenever I’ve seen automation left solely to QA specialists (who are often less experienced in coding), it has failed.

Get everyone involved with manual testing

Manual testing shouldn’t be a bottleneck owned solely by QA. Instead of being the sole tester, be the specialist who enables the team. Teach developers and product managers how to manually test effectively, guiding them on what to look for. (Note: the clearer the requirements, the easier this becomes – good testing starts with well-defined expectations). Having everyone getting involved in manual testing not only removes bottlenecks and dependencies, it tends to mean everyone cares a lot more about quality

Embedding Quality into the SDLC

Most teams have a documented SDLC (Software Development Lifecycle). But too often, these are neglected documents – primarily there for compliance, rarely referred to and, at best, reviewed once a year as a tick-box exercise. When this happens, the SDLC fails to serve its actual intended purpose: to enable teams to deliver high-quality software efficiently.

An effective SDLC should emphasis building quality in. If it reinforces the idea that quality is solely the QA’s responsibility and the primary way of doing so is late stage testing – it’s doing more harm than good.

QA specialists should work to make the SDLC useful and enabling. This means collaborating with whoever owns it to ensure it focuses on quality at every stage and supports best practices that prevent defects early. It should promote clear requirements, testability from the outset, automation, and continuous feedback loops – not just a final sign-off before release. And importantly, it should be something teams actually use, not just a compliance artefact.

Shifting from reactive to proactive

There are far more valuable things a QA specialist can be doing with their time than manually clicking around on websites. Performance testing, exploratory testing, reviewing static analysis, reviewing for common recurring support issues, accessibility. The list goes on and on. QA should be driving these conversations, ensuring quality isn’t just about finding defects, but about making the entire system stronger.

Quality is a team sport: Fostering a quality culture

The role of QA specialists should be to ensure everyone sees quality as their responsibility, not something QA owns. I strongly dislike seeing developers treat testing as someone else’s job (did you properly test the feature you worked on before handing it over, or did you rush through it just to move on to the next task?)

Creating a quality culture means fostering a shared commitment to building better software. It’s about educating teams on defect prevention, empowering them with the right tools and practices, and making it easy for everyone to care about quality and be involved.

The value of modern QA specialists

I firmly believe QA specialists still have an important role in modern software teams, especially in larger organisations. Their role isn’t disappearing – but it must evolve faster. The days of QA as manual testers, catching defects at the end of the cycle, should be left behind.

The best QA specialists aren’t testers; they’re quality enablers who shape how software is built, ensuring quality is embedded from the start rather than checked at the end.

This isn’t just better for organisations and teams – it makes the QA role a far richer, more rewarding career. On multiple occasions I’ve seen QA specialists who embody this approach go on to become Engineering Managers, Heads of Engineering and other leadership roles.

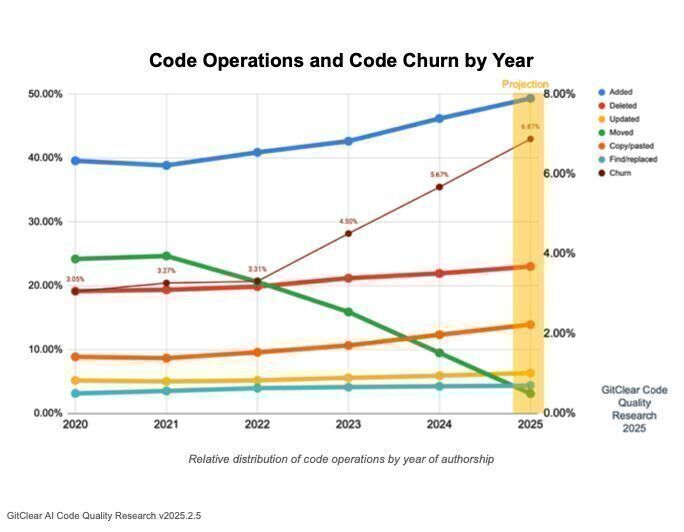

The demand for people who drive quality, improve engineering practices isn’t going away. If anything, with the rise of GenAI generated code, it’s becoming more critical than ever.