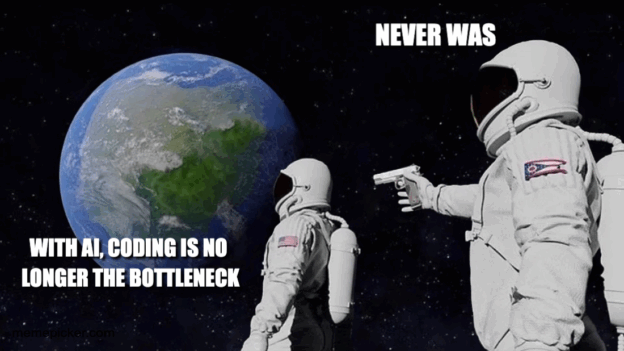

Coding has never been the governing bottleneck in software delivery. Not recently. Not in the last decade. And not across the entire history of the discipline.

I wrote this post in response to the current wave of people claiming “AI means coding is no longer the bottleneck” and to have somewhere to point them too – a long trail of experienced practitioners highlighting the main constraints in software delivery have always sat elsewhere.

That doesn’t mean coding speed never matters. In small teams, narrow problem spaces, or early exploration, it can be a local constraint, for a time. The point is that once software becomes non-trivial, progress is governed far more by other factors – such as understanding, decision-making, coordination and feedback – than by the rate at which code can be produced.

By the late 2000s, it was a meme

In 2009, Sebastián Hermida created a sticker that shows a row of monkeys hammering on keyboards under the caption “Typing is not the bottleneck”. It spread widely and became a piece of shared shorthand in the software community. He didn’t invent the idea. He turned it into a meme because, by then, it was already widely understood among practitioners.

Kevlin Henney, a long-standing independent consultant and educator, known for decades of international conference keynotes and training on software design, has said he was using the phrase in talks and training as far back as the late 1990s. The same wording also appeared in a 2009 blog post by GeePaw Hill, (a software developer, coach, and writer best known for his work in Extreme Programming), challenging the notion that practices like TDD and pair programming slow teams down.

Whether Hermida encountered the phrase via Henney, Hill, or elsewhere doesn’t matter. By the late 2000s, this way of thinking was already widely shared and known among many experienced practitioners.

Around 2000, the constraint was already understood to sit upstream

In 2000, Joel Spolsky, then a well known, prolific, blogger and co-founder of Fog Creek Software (then later Stack Overflow and Trello), published a series of articles on Painless Functional Specifications.

The articles are often remembered as an argument for writing specs, and they are. The more important point is why Spolsky cared about them. He argued that teams lose time by committing to decisions too early in code, then discovering problems only after that code exists.

You don’t have to agree with Spolsky’s preferred balance between upfront and iterative design to accept the premise. Twenty-five years ago, he was already pointing out that the limiting factor was deciding what to build and how it should behave, not how quickly code could be produced – “failing to write a spec is the single biggest unnecessary risk you take in a software project.”

Today, with GenAi there’s lots of interest in “specification driven development.” as if it’s the hot new thing. It’s not. It reflects the same underlying constraint Spolsky was describing in 2000. Across the lifecycle, code has long been, relatively speaking, easy to produce. The harder part has always been deciding what should exist, and living with the consequences once it does.

In the early 1990s, mainstream engineering literature said the same thing

In 1993, Steve McConnell published Code Complete, a book that has remained in print for decades and is still widely recommended as a foundational text in professional software development. The book was intended to consolidate what was known, from research and industry practice, about how professional software is actually built.

Drawing on a wide range of studies, McConnell showed that the dominant drivers of cost and schedule are not the act of coding itself, but defects discovered late – during system testing or after release – and the resultant cost of rework. Those defects overwhelmingly originate in requirements and design rather than during coding itself.

Even in the punchcard era, coding was not the bottleneck

Whilst programming was painfully slow by modern standards, it was still fast compared to the time it took to learn whether the code worked. Programs were submitted as batch jobs and queued for execution, with results returning hours or even days later. Any mistake meant correcting the code and starting the entire cycle again.

In 1975, Fred Brooks published The Mythical Man-Month, one of the most cited and enduring books in the history of software engineering, drawing directly on his experience building large IBM mainframe systems in the batch and punchcard era. Brooks’s essays focused on coordination, communication, and conceptual integrity – implying that the dominant challenges lay elsewhere than code production.

In Brook’s now famous essay No Silver Bullet, added to the anniversary edition of The Mythical Man-Month (1986), he made his core argument explicit. Software is hard for reasons that tools cannot remove. He distinguished between essential complexity, the difficulty of understanding a problem and deciding how software should behave, and accidental complexity, which comes from tools, languages, and machines. Decades of tooling improvements reduced accidental complexity to the point where there was, even by 1986, no order of magnitude benefit to be had from further tooling improvements.

At a similar time to the first edition of Brook’s book, in Structured Analysis and System Specification, Tom DeMarco argued for careful analysis and specification precisely because discovering misunderstandings after implementation was so expensive in batch environments.

This was already apparent even earlier. Maurice Wilkes, one of the pioneers of stored program computing, later reflected in Memoirs of a Computer Pioneer his realisation in the late 1940s, that “a good part of the remainder of my life was going to be spent in finding errors in my own programs.” From the very beginning, debugging and verification, not writing code, dominated effort.